First Monday in October: Turning Supreme Court history into tabletop strategy

Transforming the US's history of rule-making into a board game? 'I couldn't get the idea out of my head,' says designer Talia Rosen

Can we start a magazine together?

Hello. The support of subscribers reading The Generations Games keeps me motivated; paid subscribers help me to dream bigger.

I’d love to turn The Generations Games into a full-fledged online magazine.

My day job as a sub-editor and copy-editor with years of experience in layout design on national newspapers and magazines means that I’m in a great place to do this – if time and money allows.

There will always be a free version of this newsletter. However, to help that dream become a reality, please consider upgrading your subscription. You’ll also get full access to the GG archives into the bargain. Thanks!

How do you condense over 200 years of a nation’s lawmaking into a two-hour game?

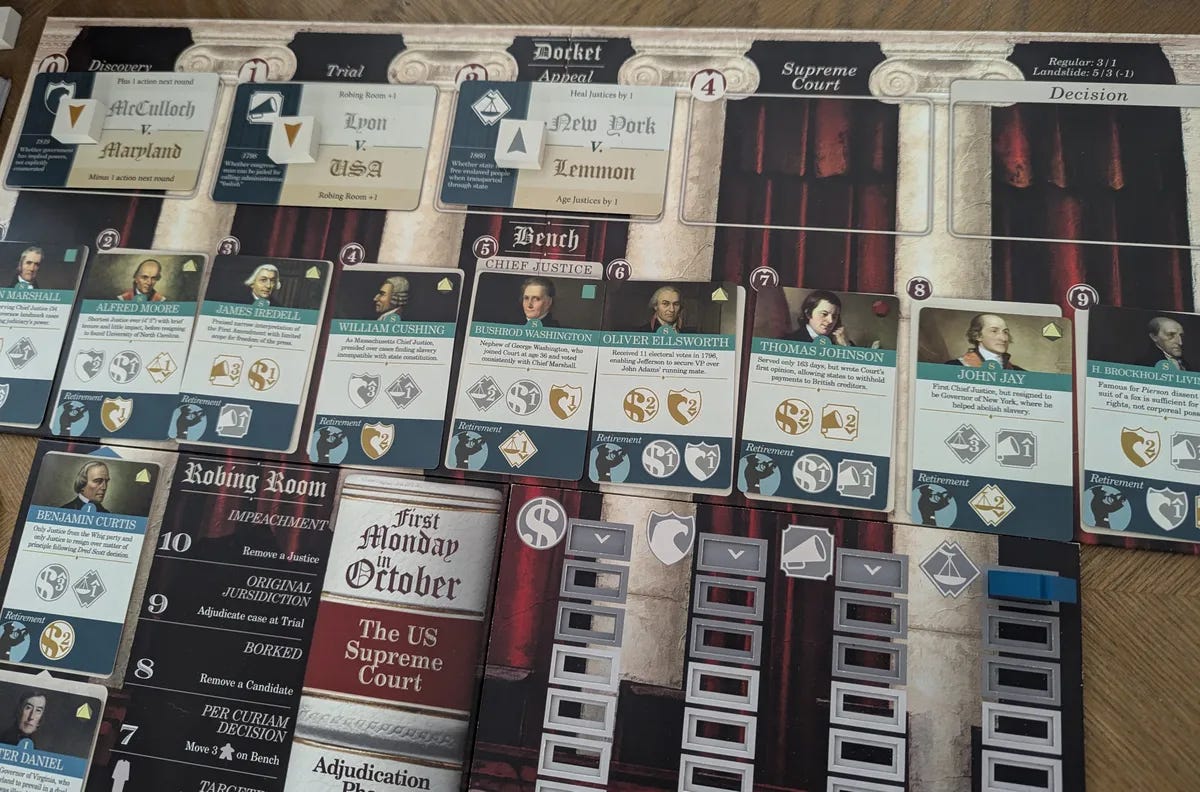

That’s the task Talia Rosen set herself. First Monday in October – named after the day when the Supreme Court starts its first session of a new term – is the result, with the practising attorney from Virginia using her knowledge of the US’s rules and regulations, and how they transpired. The country’s epoch-changing moments across three eras form the backdrop to gameplay.

It’s a curious subject to base a board game on, but then, the Supreme Court is a curious beast in its own right: nine judges, chosen by a democratically elected president, who then sit on the court for life. Nine judges who act as a final arbiter on laws passed, decide on civil rights and can rule on whether they are unconstitutional. As such, it really matters who is on that court.

Working with Twilight Struggle designer Jason Matthews, Talia has recreated the history of the court, from 1789 to 2010 in tabletop form, with each player representing a different school of thought or philosophy, who then uses their influence and the hand they’ve been dealt, to manipulate proceedings to win as many cases throughout history as possible.

With First Monday in October having been successfully crowdsourced on Kickstarter and due for a September launch through historical specialists Fort Circle Games, we spoke to Talia about the game and her other upcoming release, Kangaroo Island.

How did the idea for the game come about? Tackling a subject matter such as the entire history of the US Supreme Court feels pretty daunting. Obviously a background in law helps, but how did the process of creating First Monday in October meet your expectations?

TR: The idea came about in 2011 when playtesting a prototype of 1989: Dawn of Freedom with designer Jason Matthews.

We were talking about various ways to integrate the theme into the mechanisms of the game and about strategy game themes generally, and he remarked that he’d always wanted to make a game about the history of the US Supreme Court, but could not figure out how to do it or what the players would represent. I made a joke about the bizarre theme of parrot fish, coral, and shrimp in the wonderful Reef Encounter, and we went on our merry way.

Except, I couldn’t get the idea out of my head. I started pondering how a game about the history of the Supreme Court could work and I started thinking about the ways in which it could build on what Jason had done in his earlier 2010 release Founding Fathers.

I sketched out the basic framework for what eventually became First Monday in October, including the tug-of-war over the judicial philosophy tracks and some of the core actions. Then I did what any sensible person would do and put all of my notes on a shelf somewhere and promptly forgot about it.

It wasn’t until moving to a new apartment at the end of 2017 that I happened upon those 2011 notes, reminding myself about the seed for this game. I got to my new place, put the notes on a new shelf, and tried to forget about it – figuring that someone else would make a great game about the history of the Supreme Court that I could play instead of having to go through the trouble of making my own. This time around it was harder to forget about though and my mind kept returning to the idea throughout 2018, fleshing it out in my head, but never on paper.

Everything changed at the beginning of 2019 when I read a newspaper article about how Elizabeth Hargrave had designed Wingspan and I thought - full of hubris - that I should try to do that too. So I took the incredibly daunting step of going to the store and buying a posterboard and index cards, and I actually mocked up a playable copy of the concept.

I coerced a few friends to try it and it didn’t work at all. But I couldn’t help myself from having ideas to fix the many dysfunctional parts and I decided to bring the game to an annual April game design convention (where I had only ever been a playtester, not a designer).

I think that I was secretly hoping that the game would flop and I could put the idea to rest once and for all. Alas, people were incredibly encouraging and generous with their feedback. So I emerged from that convention invigorated and I poured a huge amount of time through 2019 into iterating on the design.

At the end of that year, I tentatively showed the game to Jason, explaining that I had been inspired by our 2011 conversation and he became a huge supporter of the design. Jason had several great ideas for further improving the design and he found a publisher interested in the game, which exceeded my wildest expectations. I suppose that’s how the idea for the game came about…

The Supreme Court is made up of nine people, nominated by democratically elected people but locked into position for life with huge powers that can impact millions of lives over decades. From an outsider’s perspective it feels like a curious part of a nation’s law-making, but also from a game design perspective it sounds like an enormously fun challenge to try to knock the gameplay momentum in your favour. What mechanics can gamers deploy to get that advantage and win the game?

TR: I love strategy board games that present players with a menu of actions, but don’t give players enough turns to do everything that they would want to do. Games like The Princes of Florence, Stephenson’s Rocket, Hansa Teutonica, and Tigris & Euphrates exemplify this style of design where you have several actions to choose from on any given turn, and you kind of want to do all of them, so you feel yourself pulled in different directions.

I love games with lots of difficult and meaningful decisions, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in First Monday in October.

The core mechanism is an action menu with six options. I’ve tried to make each option relatively straightforward and quick, so the tension comes from having to pick one of those six things to do on each turn. This is hopefully reminiscent of one of my all-time favourite games: Imperial by Mac Gerdts that builds an incredible tapestry from lots of little quick turns.

The extra layer in First Monday in October that I really like (which came from an idea during a playtest with the incredible designer Brian Mayer) is that you pick three different actions from the menu per round, but one of those actions each round will be a very powerful “supreme” version. This will allow players to significantly shape the composition and judicial philosophy of the court, but hopefully players will feel pulled in many directions about how to use their “supreme” action each round. And in a game with only 12-15 rounds per game, you’ve got to choose your “supreme” actions wisely.

‘I think you could pick any 25-year period in that timeframe and make a solid argument for it being the most significant and impactful period’ – Talia Rosen

The game depicts three eras. What are these and why were these chosen?

TR: I’m a huge fan of the stacked shuffle that games like Through the Ages: A Story of Civilization and Twilight Struggle use to randomise gameplay, while keeping a rough historical timeline in place.

So it made a ton of sense to represent 220 years of US Supreme Court history over several eras so that the deck of case cards and the deck of Justice cards could be shuffled by era to keep a rough semblance of the historical timeline.

The first era was always going to be pre-1865 to represent the legal history of the nation leading up to the American Civil War.

The second era probably would have made more sense from a jurisprudential perspective to run through the New Deal era, but that would have left too much time to cover in the third era, so I decided to run the second era through the seminal case of Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka in 1954.

Lastly, the third era runs from 1955 to 2010, so that the game remains historical in some sense.

The cases deck and the justices deck are both divided in this way, so you’ll see historical case cards and historical justice cards come out somewhat contemporaneously, but I also love counterfactual narratives, so the game can certainly see some surprising anachronistic results on the docket and on the bench.

Every generation will probably feel they live in ‘interesting’ times, but the past decade or so certainly feels abnormal. If there was ever an expansion covering this period, what elements of the recent Supreme Court would you most like to explore?

TR: I agree that every generation thinks that they live during the most important and extraordinary times. One of the purposes of First Monday in October is actually to put things in context for folks by shedding light on the first 200-plus years of the Supreme Court’s history. I think you could pick any 25-year period in that timeframe and make a solid argument for it being the most significant and impactful period.

I’ve tried to provide some of this context in the historical supplement that will come with the game. For instance, the Judiciary Act of 1801 and the facts of Marbury vs Madison (decided in 1803) are really quite remarkable, as are the facts of the World War I free-speech cases, including Abrams from 1919.

My hope is that each of the 24 cases in the game sheds light on some of the fascinating and monumental decisions that have shaped the course of history. The purpose of the game is to explore that history, which I think is foundational to understanding the present.

The game covers a lot of landmark cases from the US’s history. What factors helped you pick out which ones to include in the game?

TR: There are so many important cases on the cutting-room floor.

The key factor for picking cases is that I wanted a game that played in two hours (with the deck of cards being a reliable clock for the duration) and I wanted a game with a moderate amount of variability. Ultimately, after countless playtests, this meant that the game could only include 24 cases and that it needed to include six cases per judicial philosophy (with two cases per philosophy per era).

I really wanted the game to have a reasonable amount of predictability without players needing to know the composition of the deck. As a result, I ended up searching out the most prominent and impactful cases for each philosophy for each era. There are monumental cases that were left out because they didn’t fit neatly into one of the four judicial philosophies, and there are hugely significant cases left out because there were so many important commerce clause and free speech cases in particular.

The goal of the cases deck is to give players a sense of the progression of Supreme Court cases addressing the evolving scope of congressional authority, executive authority, free speech interpretations and applications of equality as a legal concept.

Hopefully, in just six cases over 200+ years for each of those four areas of the US Constitution, players can get a sense of key inflection points, while exploring potential alternate realities if things had developed differently.

I’ve enjoyed the game over 100 times and I’ve never seen it turn out the same way twice.

The court’s thinking can see gamers exploring philosophies that they themselves may not hold. What do you think people who play First Monday in October learn from the experience? What feedback from players has made a big impression on you?

TR: There are two types of feedback that have really stuck with me.

First, it’s incredibly common for players to marvel at the fact that many of the questions posed in each case even had to be asked, let alone how they turned out. For instance, in Era II alone, there are cases asking whether members of the public can publish pamphlets urging the cessation of weapons production during WWI and whether Congress can regulate child labour. I remember learning about the history of Supreme Court decisions in law school and being struck by the fact that things that widely seem obvious today had to be decided at some point. I’m thrilled when the game helps shed some light on how extraordinary, contentious and impactful our shared past is.

Second, the other type of common feedback is how there are not enough actions to do everything a player wants to do and this is exactly what I’m going for. From a gameplay perspective, fine-tuning the action and influence economy to force players into difficult decisions on how to use limited time and resources is definitely rooted in listening closely to player feedback and iterating on the design.

I went through at least a dozen versions of the action menu over the last few years and watching and listening to play-testers has been invaluable.

You set up a gaming club at law school, which continued after your studies were over. What’s the key to setting up a successful board gaming club?

TR: I loved getting to know fellow law students over games of Catan, Löwenherz, Elfenland and Mississippi Queen.

I’m sure the key to setting up a successful board game group will vary depending on the circumstances, but I like to think that part of my success came from my persistence and my infectious joy.

The club certainly took many months to get going and I had to keep at it, keep putting up flyers and keep organising events.

I think another key is thinking about introductory strategy games, such as Carcassonne or Ticket to Ride, rather than throwing a new attendee into the deep end right away with something like Tikal or Age of Steam.

As the organiser, you may not get to play the game you most want to play that week, but it will pay dividends down the road if you grow the hobby and actively try to foster a love for modern strategy games.

Your next game Kangaroo Island feels like quite a departure from the theme of the Supreme Court. How did it come about and what interested you about its theme and what have you carried over from the lessons learned from designing First Monday in October?

TR: The design process for Kangaroo Island could not have been more different from First Monday in October.

Whereas the design of First Monday was strongly rooted in the theme and uncovering mechanisms that would help convey the theme and history, the design of Kangaroo Island was fully rooted in the mechanisms that I wanted to explore.

I’ve always loved tile-laying games, but it wasn’t until I learned Pandoria from its designer, Jeffrey Allers, that I realised how fascinating and involved they could be. That led me to thinking about one of my all-time favourites, Carcassonne (which hangs on my wall as a piece of art) and how I’d make a game in that genre that used more of my favourite mechanisms.

As a huge fan of the scoring system and catastrophe tiles in Tigris & Euphrates, and of the player boards unlocking units and abilities in Hansa Teutonica (and of some of the unique terrain on the Eclipse map), I ended up creating a game that was designed first and foremost for me by using all of my favourite concepts.

The theme for Kangaroo Island came much later, but ended up fitting the game remarkably well.

The design process for Kangaroo Island also involved my nine-year-old son, who helped come up with several key ideas for types of terrain features to include, which have really improved the overall feel and texture of the game.

I suppose the most important lesson that carried over is to buy a glue stick because you’re going to be changing the spaces, values and key details on the player board so often, and it’s handy to just glue additional paper on top of your prototype with the changes.

The action menu in First Monday in October and the player board in Kangaroo Island both ended up being many layers deep over the years of testing and experimenting. Ultimately, it’s remarkably fun and very liberating to be able to change the game over time in a quest to find what works best, and makes the game as fun and interesting as possible.

I’m personally so excited to see these two incredibly different games come out around the same time because I’ve always had such eclectic (some might say idiosyncratic) tastes in games. I’m happy to play Imperial followed by Coconuts, then Agricola and Nexus Ops, alongside Tok Tok Woodman. Board games of all types are just my favourite way to bring people together.

As the Generations Games has a focus on family games, what are your favourite board games to play with family members?

TR: My top two choices are definitely Dixit and Wits & Wagers. Dixit is just such a perfect family game that never fails to get folks engaged and talking. Wits & Wagers is a brilliant improvement on Trivial Pursuit that has everyone getting to answer every question and no one expected to actually know the answer.

For families that like to draw, the answer has to be Pictomania or Doodle Dash, both great improvements on Pictionary, because they keep everyone involved throughout and you don’t have to be good at drawing at all to excel at Doodle Dash.

For families that want to avoid competition, then I love going with co-operative games like Mysterium, Forbidden Island, Castle Panic, Magic Maze, and The Gang.

For slightly more frenetic family fun, I’m a huge fan of Galaxy Trucker (and its spiritual brethren Fit to Print) along with King of Tokyo.

And my favourite dexterity game of all-time has to be the reverse-Jenga stacking game Men at Work, where you pile up girders and bricks and construction workers, all under the watchful eye of forewoman Rita.

For more information on First Monday in October, visit fortcircle.com. For more on Kangaroo Island’s progress, visit opinionatedgamers.com.

Tory Brown: 'There are important lessons in our past that can help us understand our present'

Two years on from the release of Votes for Women, the game's designer speaks of the response from the tabletop gaming community, and its message amid 2025's political backdrop.

Share The Generations Games? Ah, go on…

if you made it this far, you’re probably keen on family tabletop games, and games with a strong social theme. Forwarding to a like-minded friend can make a huge difference to the future of The Generations Games and our hopes to expand our output.