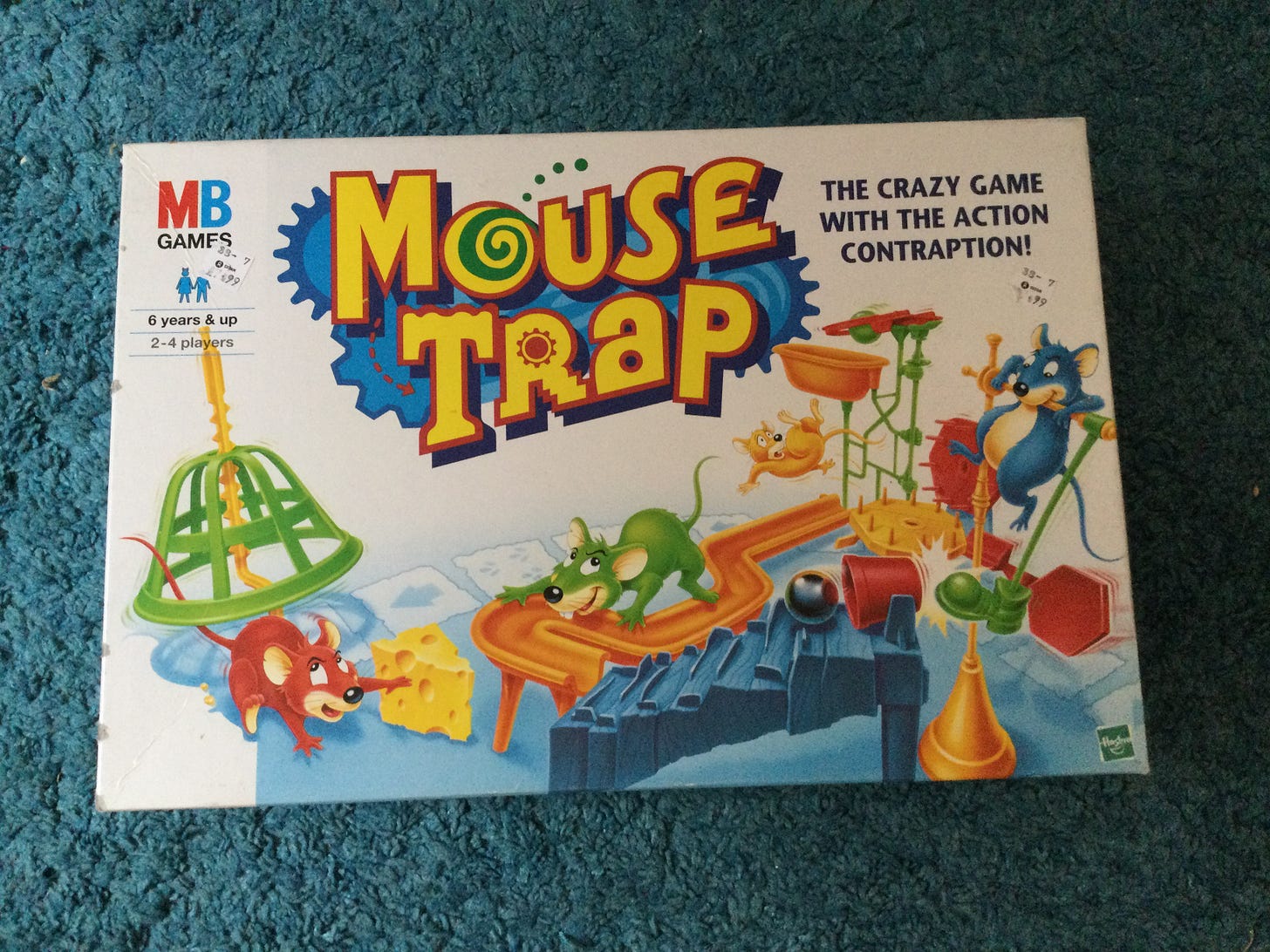

Game review 94: Mouse Trap

Is Mouse Trap a good board game? No. But its central contraption's ability to ignite a fleeting spark of childhood joy makes it worth enduring the pain, right? Also no

Michelangelo was horrified by the idea of painting the Sistine Chapel.

He resented his commission for the work demanded by the ill-tempered and controlling Julius II, known as the Warrior Pope because of his use of warfare to extend the papacy’s power across Perugia, Bologna and then Venice.

A sculptor by trade, and far more at home depicting five-metre-high stoneworks of naked prophets, the artist feared his public humiliation in the face of the unprecedented task, depicting humanity’s story – as told through the Old Testament, from Genesis to the fall of man, then to the second coming of Christ and the species’ ultimate last judgement – across 12,000 sq ft of barrel-vaulted ceiling suspended more than 20m in the air.

But despite his agitation and paranoia, Michelangelo proceeded regardless. He did not revel in his labour. The four years it took him to complete his monumental fresco’s nine panels – with his head craned upwards, stretched arm aloft while balancing on shaky scaffolding – left him in lifelong agony: a throbbing pain thrummed from his swelled neck, his vision degenerated by the conditions and the gloom. Vertigo gripped.

“I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture,” wrote the legendary Renaissance master to his friend, Giovanni da Pistoia, about the ordeal that his efforts and genius rewarded him with. He continued:

“Hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy (or anywhere else where the stagnant water’s poison).

My stomach’s squashed under my chin, my beard is pointed at heaven,

My brain’s crushed in a casket

My breast twists like a harpy’s

… every gesture I make is blind and aimless

Because I’m stuck like this, my thoughts are crazy, perfidious tripe.”

Yes, Mickey, we hear you, mate. Because this is an anguish familiar with any parent confronted by their delighted, excitable offspring carrying in their possession a copy of the classic board game Mouse Trap.

“Mouse Trap! Let’s play Mouse Trap!” my daughter, E, exclaims in front of our board game collection. The 2014 Spiel des Jahres winner Camel Up sits undisturbed on the shelves. The game-changing Catan is a no for now. A visible Twilight Imperium, which plays out 17 interplanetary factions vying for economic, military and political domination of the galaxy, strategically twisting and turning across 10 hours of play, goes ignored. Instead, Milton Bradley’s, now Hasbro’s, torture device grabs her attention.

Why? The image of Mouse Trap’s contraption, that’s why. Note, not the contraption itself, lying strewn like rubble in about 25 pieces across the length of its cardboard sarcophagus. The image on the front. The one selling the dream.

You know your limits. You know the physical and mental exertions that await once the task begins. Your brain and body cry out. no. we must not. we have pursued this provocative path before – tread not along its trail again, for all will be lost. all this has been foreseen. all this will be again.

But that smiling, upturned face! That giggle of anticipatory glee! Of course you open Pandora’s box to confront its contents - a dizzying and overwhelming array of bewildering components: What is this thing that looks like a spiky road sign? What are all these rods for? Why is there a bathtub?

Soon you’re rolling a die – for what purpose? To move a plastic mouse along an arbitrary path, to fulfil a binary rodent destiny of cheese or entrapment. Amid that dispiriting scenario you’re connecting bright plastic tubes on to frustratingly fiddly ratchets on a quest that feels as dispiritingly pointless as Sisyphus insisting that his bloody rock must get up that hill. Sure, you may not be developing an acute form of nystagmus like Michelangelo did, but I wouldn’t rule out some form of twitch.

But still that grin beams at you. So you continue your reluctant, dutiful obligation, stupid parental love and all.

An illogical, ugly construction kit that comes with a rule book, only to be completed after certain luck-based criteria have been fulfilled: a tedious set-up and unstacking process; limited, even non-existent player agency, with its space commands dictating rather than discussing (Take that cheese! Build that thing! Do as you’re told!); a gruelling, uneven pace.

Even after the roll-and-move dynamics drag and drag, overcome all that in your Herculean efforts of endurance and you face a tortuous, never-ending end game: the dreaded ‘loop’ – has any game mechanism summoned such feelings of tedious terror, a fever dream of slow-motion, inevitable doom, as our mousey components go round and round and round, only a precise roll of the die will land on the singular correct space ensuring that the trap is set and can finally be deployed.

But even when everything is assembled – a marathon of boredom run following the most delayed of gratifications – there’s the risk of experiencing the purist distilled frustration in that elaborate contraption, the game’s raison d'être, failing to fulfil the one job required of it: sparking that moment of elation. The ball will drop, the seesaw may swing, but that diver will miss his target when primed on centre stage. The one thing we all came to see was a mouse, trapped. But it remains uncaptured, prolonging the players’ torment. We beat on. Roll. And Move. Roll. And Move. Oh, go back six spaces.

Mouse Trap, on all conceivable levels, fails as a game. Bar one: as a provider of overwhelming, childish, anticipatory delight. And the ensuing rose-tinted nostalgia fuel it provides. There, it wins hands down.

Because we don’t ever really remember playing Mouse Trap, do we? Any of us. Did we actually play it, even in our infancy? What we do remember is the excitement of seeing that central device, that incredible-looking contraption, perhaps shining out from the pages of a catalogue, or pride of place on a toy shop’s shelves.

For Mouse Trap’s original 1963 design was innovative: perhaps the first 3D board game ever put to market, it literally added an extra dimension to the play experience for which other, better games could build on. And what is art for, but to recapture that sense of childhood excitement of exploration, anticipation and curiosity that such an experience provides – that sense of what if? Why do we play games if not for that singular spark of unbridled joy?

But still, alas, Mouse Trap suffers from, and inflicts its suffering, in the same way that Domino Rally sets were for many kids among the first items on the Christmas or birthday present list but rarely played with once bought. The expectation is exhilarating; the reality and result, tedious. Well, unless you’re one of the artistic visionaries of the medieval age and able to accomplish one of humanity’s creative triumphs while developing back ache. But you get the idea.

But even though Michelangelo poured his soul into the Sistine Chapel’s phenomenal imagery, enough to fuel the discussions of art critics for centuries, and to continue them for centuries more, show your kid a picture of his God and Adam, their hands reaching across to each other, in a gesture symbolising the ultimate creation – life itself – and you’re likely to be met with a shrug before their attention turns to the TV screen depicting members of The Loud House family overcome by the green stink fumes emanating from a row of Portaloos they’ve just crashed into. (Admittedly, when I ran this experiment with E, after a good deal of ducking and diving to keep her eyes on the screen and an exasperated “I’ll have to rewind that bit now!” Michelangelo’s magnum opus did elicit an: “It is quite cool, though.”)

However, despite the suffering it delivers in its creation, the ennui conjured in its processes, as sanity unsheathes itself from its host and all seems lost, get a parent to show their young loved ones the constructed Mouse Trap contraption and hand them a ball bearing, and you’ll witness a reaction as visceral as any you could expect during any Rapture you could care to mention.

And sometimes, after all the endurance, the gruelling tedium, the contraption actually works. As young limbs flail around you and their spirited, spontaneous shrieks form in the air at your mouse’s capture, you finally understand that the idea of play, the concept of our freedom and our need to express, is more powerful than the play itself. For in that moment, whether thanks to a higher being or sheer dumb luck played out at an eternal, infinite, cosmological level, we witness the ultimate reward: a part of the universe that has been switched into being, into creation, experiencing what it feels like to be truly alive.

Maybe it’s a masterpiece, after all.

Game facts and stats

Age

6+

Year first published

1963

Publisher

Milton Bradley/Hasbro

Designer

Gordon A Barlow, Marvin Glass, Harvey ‘Hank’ Kramer and Burt Meyer

Player count

2–4

E’s review

What do you like best about the game?

“So, I like that we can build it along and we can try to get the other person. We get to make the foot kick the bottle and go down the stairs.”

Is it tricky?

“Really difficult, because we sometimes do not know where things go when we’re setting up.”

50/10

My review

Set-up time

Well, that’s a deep question that gets right to the nub of Mouse Trap’s issues, right? Mouse Trap’s initial game play is easy and quick to put in place. It’s the fact that you have to create the finished board across the game itself that’s the issue. And thanks to the seemingly endless, circular roll and move mechanics, that means this set-up is not quick. You could be going into above the hour mark.

Price

You could probably get a copy at any old thrift or charity store for under £4 ($6). Whether it’ll have all its set pieces is another matter. Hasbro’s latest versions of the game, desperately proclaiming an easier set-up than previous editions on its front, can be bought new for £22 ($29). Complete, vintage Milton Bradley versions are going online from anything from £10

Practicality

No.

Fun for parents?

Imagine, for a moment, bringing Mouse Trap out at a games’ night with your grown-up chums. All the games in the world, and you’ve chosen a 50-minute roll-and-mover, during which you and your friends must attempt, but fail, to construct a Rube Goldberg-style contraption devoid of any of your own individual imagination or creativity. Yes, Mouse Trap is a curio – a provider of the pursuit of a momentary feeling of elation. But do you actually want to play it to gain it?

2/10

Like this? Why not try…

Share The Generations Games? Ah, go on…

if you made it this far, you’re probably keen on family tabletop games, and games with a strong social theme. Forwarding to a like-minded friend can make a huge difference to the future of The Generations Games and our hopes to expand our output.

I remember buying it on a flee market as a kid based on how it looked

I haven’t been as disappointed as I was then since