Tanya Pobuda: 'What happens to game publishers who aren't inclusive? They fail'

The board games industry researcher and trainer on why it's important for players to see themselves and their interests represented in games

Can we start a magazine together?

Hello. The support of subscribers reading The Generations Games keeps me motivated; paid subscribers help me to dream bigger.

I’d love to turn The Generations Games into a full-fledged online magazine.

My day job as a sub-editor and copy-editor with years of experience in layout design means that I’m in a great place to do this – if time and money allows.

There will always be a free version of this newsletter. However, to help this dream become a reality, please consider upgrading your subscription. You’ll also get full access to the GG archives into the bargain. Thanks!

Does it really matter if your interests and image are represented in board game themes and artwork?

If you’re an average white chap who likes sci-fi, sports car racing, zombie movies, dinosaurs, peg-legged pirates and, er, rampaging colonialism, then what’s the problem? Everything’s catered for.

I mean, this all describes this author right down to a tee. Well, apart from the latter interest – though my growing, substantial board game collection strongly suggests that I have the same grab-all-the-things-hoard-them-all spirit possessed of my globe-trotting plundering countryfolk who subsequently filled the British Museum. So, what’s the problem?

Well, maybe Tanya Pobuda can help me out here. The board games industry researcher, instructional designer and trainer researches gender and racial representation in the hobby. Her PhD, "I Didn't See Anyone Who Looked Like Me": Gender and Racial Representation in Board Gaming, found that “92% of the labour of board game design was that of white-identified, male-identified creators”.

What are the real-world repercussions of a stat like that? How does it impact gamers and the industry itself? Tanya states that her studies were speaking to “large publishers and their financial backers about how representation, diversity and inclusion is a serious risk management challenge for their future growth”, and that her research found accounts of “reported unwelcoming and even threatening behaviour at friendly local game stores”. Does the concept of gatekeeping – the controlling and limiting of access to an industry, interest or pastime – have a role to play in linking these strands?

With diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programmes under threat from governmental and corporate elites, we spoke to Tanya about her research and asked why tabletop game publishers and players should consider DEI actions a worthwhile endeavour.

‘After contracts and clients in the military, automotive, tech, life sciences, I have never encountered quite the level of resistance and, frankly, vitriol as I have conducted this board game research. That, in and of itself, is another fascinating finding’

"I Didn't See Anyone Who Looked Like Me" is the statement that forms the basis of your PhD into representation in board gaming. Why did you want to study this matter?

TP: I'm a former senior communication, marketing and research and development (R&D) professional with 27 years experience in the high tech and life sciences sector. My background is in creating corporate dashboards for senior leaders, conducting audience and marketplace analysis.

I loved board games and thought I'd do my corporate processes for this hobby and sector. I used all of the same methods for my dissertation, audience and environmental scans, market segmentation and size analysis, that I would have used when I worked for multinational agencies as a director, except my doctoral research was a far more rigorously ethic-approved, peer-reviewed process.

My dissertation was an attempt to speak to the proverbial money in the board game sector. It isn't personal, it’s just business, just math. That was my job in industry, to help floundering companies expand. Once you've established a beachhead in your market, your supply lines are secured (revenues are coming in), that’s when it becomes an imperative to radiate out, expand into new territories or, in this case, new audiences. That's when you, to borrow the parlance of the venture capitalists I used to work with, start making the 'grown-up money'.

In my nearly 30 years in industry, I watched organisations fail dramatically because they adopted the comfort-zone mindset of doubling and tripling down on an existing audience. The tech companies that did this back in the early days of computing are now barely a footnote in history.

I get change is scary but in the current market it is an imperative. Companies have to innovate and expand or die. A lot of organisations have simply not learned this lesson. Indeed, they are being pulled back from it.

As an aside, I can share that after contracts and clients in the military, automotive, tech, life sciences, I have never encountered quite the level of resistance and, frankly, vitriol as I have conducted this board game research. That, in and of itself, is another fascinating finding. It is another dynamic (as I share in my final report and dissertation) about which the sector should be deeply concerned, as it also dramatically delimits the financial growth and flourishing of the sector. This aggressive and, at times, violent gatekeeping stunts and stultifies the growth of the entire sector.

If you want to see how allowing no-holds-barred racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism impacts a business, look at Twitter as a case study, which has lost an estimated 84% of its value. Elon Musk recently stated at the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) that he purchased Twitter for $44 billion and it is now worth “eight cents”.

Your research found that “of the human representation found on the cover art of the boxes of the top 200 BGG [Board Game Geek] games, images of men and/or boys represented 76.8% of the sample” and that white figures on the cover art of board games made up 82.5% of the total. From your research, what impact does not seeing yourself reflected in an industry or hobby have on an individual?

TP: Cover art, in particular, is a form of marketing. Representation is a marketing decision. And when people don’t ‘see’ themselves in the product, they can’t imagine themselves using that product. And it impacts bottom-line results.

Indeed, demographic representation in the marketing and advertising strategies of consumer products has been correlated to increased sales and higher revenues (Henderson and Williamson, 2013).

Here’s a concrete example in film: A study of box-office returns on 109 Hollywood films confirms the unprofitability of racial and gender homogeneity, uncovering that it can cost big-budget films as much as 20% of their budget in losses on opening weekend when there isn’t robust and authentic representation of BIPOC and women in the film production and on the screen; for a $159m film, the production will lose $32.m opening weekend (Higginbotham, Phil, Zheng & Uhlis, 2020).

Indeed, demographic representation in the marketing and advertising strategies of consumer products has been correlated to increased sales and higher revenues (Henderson & Williamson, 2013).

Overall, media, which includes board games, plays an important role in the socialisation and enculturation of members of a community, helping to shape daily behaviour, performative gender roles, education and career paths, how they speak and act, and what values they engender. Popular media such as the films we watch, the books we read and the games we play act as part of a system by which we, as a culture, transfer ideological ideas, values and beliefs.

Audience analysis tells you major markets are changing demographically. From my research, a survey of diverse, avid board gamers are sharing that there is a problem with representation and that they care about it. And that it impacts their play and purchase decisions. I’ve been really surprised about how little interest there was in engaging with my research in the wider industry. That’s another finding.

Overall, if your product advertises mostly to white men and is mostly made by white men, sharing themes that resonate and appeal to that ever-shrinking demographic – less than 10% of the world’s population, incidentally. If I were consulting with publishers (a job I used to do before I returned to my PhD), I would share with them that this is a most unhealthy state of affairs and you likely won’t survive if you continue to haplessly cling to it as your only audience.

‘What about the folks who took a look around and simply said "nope" in search of another hobby? It is hard to locate these people because even for the avid players a significant portion indicated they do not engage in online forums that feature board game topics for fear of abuse and reprisal.’

You mention in the research that representation gaps in board game design and artwork “creates a vicious circle of exclusion”. What do you mean by this?

TP: The contemporary board game landscape has an observable lack of representation in playable characters, artwork and game themes, as well as a lack of participation by women, BIPOC and other marginalised players in game design, conventions and online forums.

A systemic lack of representation is one possible barrier for girls, women, and individuals who identify as BIPOC from engaging with board games. People are told in a myriad of ways board gaming isn’t for them. Gil Hova [The Networks game designer] wrote a great piece wherein he noted that board gaming is still surrounded by “a bunch of invisible ropes that keep many women from enjoying the hobby”, one of which, he noted, is the lack of representation within the games themselves.

This symbolic exclusion, in turn, can play a role in preventing communities from gaining the necessary literacies required to engage in gaming.

This, in turn, then creates the conditions for a systemic lack of diversity in the games industry, creating a vicious circle of exclusion. While women and other marginalised players can freely purchase and play games in theory, a myriad of social, economic and ideological conditions exist that create a kind of “cultural inaccessibility” of games and gaming for certain communities.

White male designers tend to make games for white male gamers. Layered on top of that recursive and exclusionary reality, there are the overt expressions of symbolic violence such as incivility, trash talk, harassment and so-called alpha gaming whereby individuals dominate game play, making decisions and playing for marginalised players. In these settings, symbolic violence can lead to actual violence.

You received responses made by women, non-binary, trans and/or BIPOC gamers to surveys that detailed receiving unwelcoming or even threatening behaviour while engaged in the hobby. You also had responders stating gaming is “one of the most inclusive environments” they have encountered. Why is there gatekeeping in the sphere and what’s the key to unlocking things so the latter can override the former examples?

TP: Respondents said "you have to have thick skin" to become active in the hobby board game community, noting that marginalised players needed to be "resilient" and "stubborn" to stay in the hobby. But they do it because the lure of gaming is that strong (because everyone loves to game. Heck, primate studies confirm that puzzle-solving and play are integral parts of primate motivations).

What about the folks who took a look around and simply said "nope" in search of another hobby? It is hard to locate these people because even for the avid players a significant portion indicated they do not engage in online forums that feature board game topics for fear of abuse and reprisal.

These dynamics all limit growth for the sector. It has become a risk management and a massive business problem.

What dangers are there for publishers who aren’t inclusive?

TP: I wrote a piece for Analog Games Studies that discusses this.

The short answer is that these businesses fail.

Here’s a quick story about two case studies to show how this story ends.

As a former tech reporter, I see parallels between board gaming and the early days of the personal computing industry. In the early 90s, I worked as a reporter and later, a communication advisor to technology companies in Canada and the US. One very well-known company, today part of the so-called Frightful Five (Facebook, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Apple), had a corporate performance model that was focused almost entirely on market expansion.

When I did work for this company, I experienced first-hand how doggedly focused this technology giant was on expanding out from its beachhead market of white, male middle-class 'early adopters'. This company’s entire goal was to create interest in personal computing among different demographics and walks of life, from kids, moms, and grandparents to specific industry sectors who could benefit from automation.

This tech giant worked to create computing literacies and expand its addressable market for computing software and hardware, driving up broad-based interest in personal computing. This company spent the lion’s share of its marketing budget relentlessly driving expansion initiatives and wooing new users. This technology leader gave stuff away, held computing literacy workshops, and hired personal computing evangelists to roam Canada and the US, winning friends and influencing people in untapped, underrepresented communities, and market segments. This company now runs workshops on cruise ships and retirement communities to provide computing literacy to ageing users. This strategy worked. This client thrived and grew into a titan of the global marketplace.

However, this was not the fate of another technology client of mine. This ill-fated hardware and software company no longer exists: its technologies were subsumed through acquisition by another hardware company, which, in turn, also no longer exists. The client that failed was infamous for its technical elitism, focusing on a small pool of scientific and technical users, to the exclusion of any other markets. This client even had a president who said, "(t)here is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home".

There was an elitism that pervaded the ranks of this organisation, one arguably rooted in a gendered and racialised understanding of their marketplace. They thought that spending any time on expanding their base was a waste of time and resources. I both see and hear a similar kind of blinkered, elitist view, grounded in myths about gender and race, in corners of the board game market.

There’s a focus on an imagined audience of ‘real gamers’ and the ‘real addressable market’ that seems to be rooted in a familiar sounding elitism, the same lack of imagination about addressable markets. It was these same discourses and debates that pervaded the early days of personal computing within some of the companies that didn’t survive. While the companies looked out beyond their comfortable and familiar base of users, and cultivated broader audiences, they did not only just survive but they thrived.

I talk about this in my podcast

I think we are seeing some of that bad decision-making playing out right now. And in the impending trade war, these costly, production-heavy games will be even more out of reach for consumers and even more in search of a market that frankly no longer really exists as a viable target.

Let’s face it, the consumer market of wealthy white men is already over-saturated. How many YouTube videos do we see about “culling” massive board game collections? The market needs to radiate out or the sector will continue to falter.

How does everyone benefit when more people see themselves represented in the games they play and in the groups they play them with?

TP: Representation in the media is so important for the reasons I shared in my discussion of marketing. In early studies of video game acculturation, there was an observed hardening of gender-based dividing lines around gaming, with researchers reporting kindergarten-aged female children viewing video games as being a boy’s pastime.

In the early days of video gaming and the rise of the arcade, while women and girls were found to have a positive impression of gaming and arcades, they made up only 20% of the arcade players.

What was at work there? The subtle and not-so-subtle messages that I’ve heard innumerable times online, and in gaming spaces that games might not be for girls and women or other marginalised intersectional identities, or might not be a cultural practice that can be enjoyed, understood or mastered by marginalised players.

That came down to a lot of the same things that I found in my board game research. It wasn’t advertised to girls and women, and the gaming spaces weren’t always socially or physically safe for women and girls to be in. That message is being delivered again loud and clear in board gaming.

These overt and tacit messages about gaming can also lead to something called the stereotype threat. This occurs when an individual feels themselves at risk of behaving or performing in a way that reinforces gender or racial stereotypes.

I did this great interview with a long-time board gamer. I’ve changed her name to protect her identity. Micha shared her broader concerns for the board game publishing industry if it continues not to embrace greater diversity and representation in its games, and nurturing inclusiveness within its communities. Micha believes that the industry’s growth is at stake:

‘It is a risk management issue. And that I do believe that lack of diversity is an industry growth issue. It is a capitalistic issue for our industry; but on the softer side, I think that people inherently look for themselves. It's why when you look at clouds you're looking for a face. It's why when you see that weird, mottled pattern on a tile in your bathroom, you see shapes and you see faces. ...That's how basic our need to see ourselves in the world is. So, you want to elevate that. You want to see yourself. In your community you want to see yourself and in the activities you care about.’

In what way do you feel tabletop games can facilitate communication and conversations on social issues?

TP: Games of all kinds have played a key role in the creation of identity through the creative spaces that games allow players to carve out in their lives. Players can enjoy, through the qualities of games, transformative acts of identity creation, trying on new personas, and allowing gamers to have new experiences in the low-penalty, experimental game state

Nakamura (2000) has called video games and cyberspace play a kind of “identity tourism” and I love this idea so much. Board and video games become simulations of “worlds or problem spaces'' for the accomplishment of desired outcomes that might be outside of our own specific perspectives and worldviews. Players can literally try on other personas, and perspectives, allowing individuals to create and construct identities.

I was reading this great thesis about the tabletop role-playing game Shadowrun. Merriman (2017) discusses the opportunity for “players to be someone other than themselves, it provides a space for roleplay and for players to try on alternate identities”.

Gaming can take us out of a potentially blinkered and compartmentalised perspective, and into the lives and systems of others that we might not encounter in our day-to-day realities. Games can act as models or “miniaturised” systems enhancing a person’s ability to view problems from an isometric, God’s-eye view of complex systems and dynamics, and helping people analyse, interrogate and experiment with solutions thus broadening empathy and building social systems literacy.

We learn through game play as children. Playing with models of human processes (such as dolls, toy houses, etc) can help children to later assume adult roles in later life. Games-based identity play occupies a key role in the formation of self and helps individuals understand their place in a wide social context.

Words count as well as images in this scenario. What can publishers do in, say, rule books to improve representation as well as understanding?

TP: My co-author and I wrote about the ways rulebooks can be improved to welcome more people into the hobby. You can see from the piece, a representative sample of the “cream of the board game crop’ are failing to do even the small niceties of inclusion well. There are a lot of actionable tips in our article for how to fix that”

We include these thoughts at the end of the piece about, in particular, gender inclusion. At its best, board gaming is all about invitation, sharing and community. As players and fellow members of the community, if we knew that something we were doing was creating a less welcoming space, we’d want to know – we would want to correct the misstep, we’d want a chance to try again, and do better.

This is the spirit of continuous improvement; this is innovation. The desire to learn, grow, innovate and include is what creates, and maintains, a community.

With attacks on DEI measures taking place among political and corporate elites taking place, what would be your message to game designers worried about what this may mean for their games getting published?

TP: Oh, the attacks on DEI will be the undoing of many businesses, including publishers. Diversity improves the bottom line. Innumerable studies demonstrate this.

There are some systemic myths in production and publishing that media properties with prominent representation of women, for example, will generate less profit.

Family films with a woman in the lead role generated 7.3% more profit than those with men in the lead; family films with people of colour in the lead generated 15.4% more revenue, grossing $21m more than those with a white lead character.

Diverse teams are more likely to generate creative solutions and new ideas due to their varied perspectives and backgrounds. Companies with more diverse management teams generate 19% more revenue. I did a video about this a while ago.

Which games have you played from the past few years that you feel have shown the way in how representation can be done well?

TP: It is weird you should ask about this now. There’s a new gamebook, Hikikomori, A Lucky Lockdown Life Sim by Swiss-Canadian game designer and author Derek Schraner, which is a post-capitalist meditation on the relentless demands of daily survival in a world of income inequality, epidemics and pandemics. It takes many of my thoughts about how representation can be handled to welcome everyone and allows everyone to see themselves in the game play.

This unconventional, genre-defying gamebook is also a conceptual art piece, which speaks to the mishandling of Covid-19, the new global pandemics fast nipping at its heels, and the exploitation of working people. It is also a casual game that can be played everywhere with just a pen and a handful of dice [or a free dice app on your phone].

The gamebook and its theme spoke to me. Schraner has been living for five years in a self-imposed isolation to ensure a vulnerable family member is safe during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. They have spent decades studying games as art forms and experiences. Hikikomori is the first in a series of games based upon the culmination of that deep and dedicated research.

This game is designed to appeal to a wide range of gaming literacies. People who might be new to gaming can understand it. I think there is a critical need for casual gaming in board games. Most of us have zero time because we are struggling to survive. I think gamebooks like this one are the future for analogue board games as our free time dwindles, and money gets tighter and tighter for us all.

Board gaming’s history is rife with co-opted ideas or erasure of marginalised communities having their designs stolen. Are there any games from the past that you can think of that could be turned on their heads to deliver a more representative message?

TP: Derek is also working on a new game that is a love letter to life in Toronto and Canadian content in the 1980s. There’s a new wave of Canadian pride in response to the 47th American president's (I don’t like to say his name) annexation threats. We need a lot more Canadian content right now and we need to celebrate it. It feels essential.

As the Generations Games has a focus on family games, what are your favourite board games to play with family members?

We have so many board games in our home, roughly 3,000-plus, that is such a hard question to answer.

My household has been so busy making things and struggling to make ends meet lately we’ve had no time. But we love games like Star Realms and Ascension. Deck Building is our thing in this house.

For more information, visit tanyapobudaphd.com

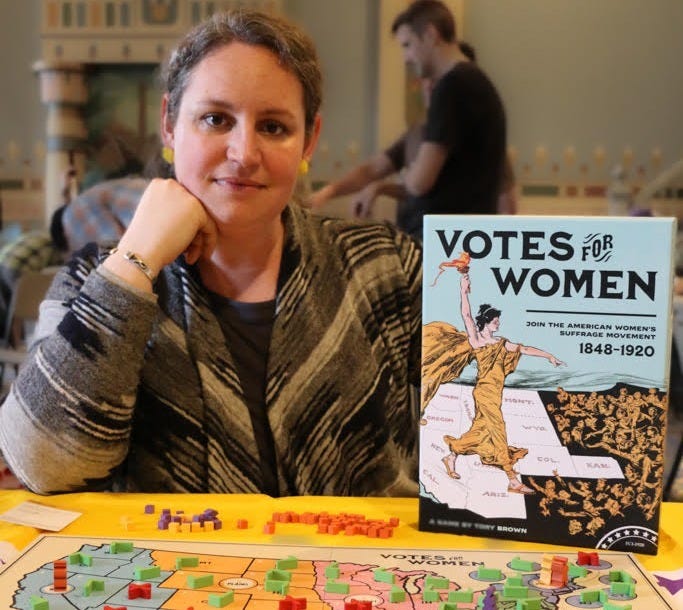

Tory Brown: 'There are important lessons in our past that can help us understand our present'

Two years on from the release of Votes for Women, the game's designer speaks of the response from the tabletop gaming community, and its message amid 2025's political backdrop.

Share The Generations Games? Ah, go on…

if you made it this far, you’re probably keen on family tabletop games, and games with a strong social theme. Forwarding to a like-minded friend can make a huge difference to the future of The Generations Games and our hopes to expand our output.